Have you come across CERCLL yet? The Center for Educational Resources in Culture, Language and Literacy at the University of Arizona (https://cercll.arizona.edu/ ) is a Language Resource Center that supports research related to language teaching and learning and provides educators with quality resources for teaching and professional development, including some really interesting webinars.

On 18 April, Regina Kaplan-Rakowski from the University of North Texas spoke about the various forms of extended reality and gave some hints for making use of them in language teaching. Some of her suggestions are things that language teachers could be doing right now; others might need to wait until the necessary technology becomes more accessible. Here are some of the main takeaways from the webinar.

Extended reality (XR) is currently divided into three main forms: AR – augmented reality; MR – mixed reality; and VR – virtual reality. As polling of webinar participants showed, VR is probably the best known of these, although most of us will have come across AR, which is commonly used in many apps.

Augmented reality (AR) is a form of immersive technology, which combines real world and digital content (eg text, images), usually on the screen of a smartphone or computer. The virtual backgrounds and video filters on meeting tools such as Zoom are examples of AR, allowing the user to combine both real world and digital content at the click of a button.

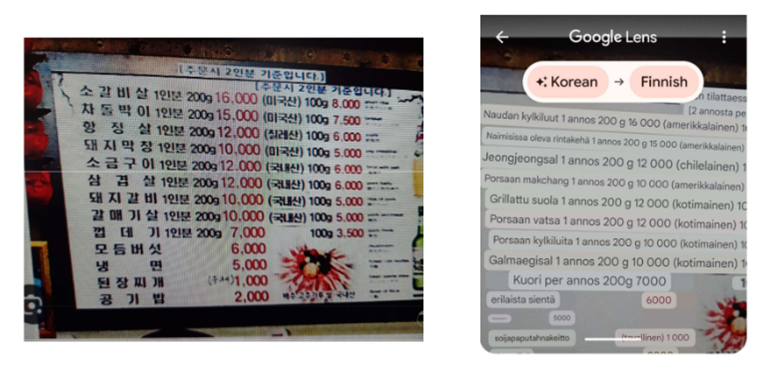

For language teaching and learning, AR is already with us in the likes of Google lens (through the app of the same name or online at https://lens.google). Users can select the languages that they wish to use, then point their phone camera at a text, or upload an image that they wish to have translated; the app then provides translations directly in the image. Similar apps include the likes of Papago (for Korean), and DeepL Translate. (Mondly also offers an AI language teacher, but the app requires a subscription for the full experience.)

The translations that these apps produce are not always perfect, as the screenshots of translations of a Finnish sign on the left show (Google lens on the left, DeepL on the right: Google is more accurate in this case). But they do give language learners some help with understanding texts in the language that they are learning, and can help boost interest and motivation.

How to use these apps in language learning? In the classroom, learners could be given images with text in the target language and use their smartphones to translate to their L1. The teacher could ask them to look out for particular items of vocabulary, or to compile their own list of new words based on what they have discovered. Images could include for example realia such as shopping lists, menus, adverts from grocery stores, information about hotels and so on. Learners could go for a “walk” on Google Streetview and translate the signs that they see or visit a virtual museum and read the signs and the labels there. Integration students who are learning the local language could be asked to decipher the signs they see all around them.

When visiting a new country in person, learners can use these AR apps to help them get to grip with the local language; they can scan words in the foreign language and learn the meanings of what they see. For a more structured approach to language practice, they could be set challenges in the target language which involve finding information from local sources and/or navigating around a new city. This type of gamification involves engaging with the language more deeply, as well as interacting with locals and collaborating with other learners. Anecdotal evidence shows that users have found such quests engaging and motivating, although academic research in the field is still in its early stages and no firm conclusions have yet been drawn.

MR mixed reality is a combination of AR + VR, which allows users to physically interact with virtual objects within the real world. XR devices scan the local environment and then superimpose digital objects on it, giving the user the impression that they exist in the real world. A user might create a hologram image and then move it around in the real world: drawing and then arranging hologram flowers on a table, for example, or turning a globe to view it from different angles.

Devices needed to experience MR include the likes of Oculus Quest pro, Google Glass, Magic Leap and Apple Vision pro. At present, the cost of such XR glasses is high, meaning that access is currently limited; but Prof Kaplan-Rakowski argued that the same applied to smartphones in the early days, and that prices will drop – and accessibility increase – as the technology advances.

Given the high cost of devices, MR use has mostly been restricted to fields which really require users to practice complicated procedures which would be hard to practice in real life: surgery for example. Possible uses for language teaching could however involve activities which involve manipulating objects: cooking a dish, creating an art work or labelling the objects around them in the foreign language, for example. Once again, the immersive experience can bring languages to life and increase motivation of learners.

The final and most immersive form of XR is VR – virtual reality. Users wear a device which blocks out the real world completely (sight, sound), and then immerses them in a computer-generated 360-degree space which can seem completely real to the user. (Other devices such as VR haptic vests can go further and add sensation to the visual and auditory elements.)

Some VR devices are fairly cheap and cheerful: Google cardboard, for example, allowed users to insert their smartphone into a cardboard headset and view a 360-degree image of what was projected. Other cheap devices operating on the same principle still exist. Most VR headsets are however very expensive, and the possibility of being able to use a full set in class seems remote, at least until the prices come down.

VR could however allow a learner to visit a new country and to experience different situations as if they were genuinely real. The Wander app, for example allows you to travel anywhere in the world. The Immerse and ImmerseMe apps allow users to practice language in context in 40 authentic different settings; they could, for example, have a conversation on a beach whilst at the same time seeing and hearing the ocean. Learners can discuss with avatars and get immediate AI (Chat GPT-based) feedback. Language becomes more real, and communication skills can develop faster than with simple classroom exercises.

Research has shown that VR is extremely engaging, develops empathy, and gets learners motivated. It has furthermore been demonstrated that many users find it less stressful to use a foreign language in VR sooner than in the real world. Foreign language anxiety is distracted by interesting settings: learners feel freer to make mistakes when the setting is not real and do not feel judged when feedback is given by an avatar sooner than a real person. When presenting in a virtual classroom sooner than in an online meeting such as Zoom, users see only virtual faces of the audience, sooner than real people; this reduces stress, but participants are still able to interact with one another as normal.

At present, the cost of equipment means that MR and VR is out of reach of most classrooms; but in future these technologies have the potential to add greatly to the language learning experience, and they are worth keeping an eye on. In the meantime, teachers could perhaps encourage those who already own the necessary VR equipment to make use of some of the apps available to further their language learning.

With AR translation tools already widely available to those with smartphones, these offer perhaps the best opportunities for integrating real world and digital content into interactive activities that will boost student engagement and increase motivation. How can you make use of them in your teaching?